|

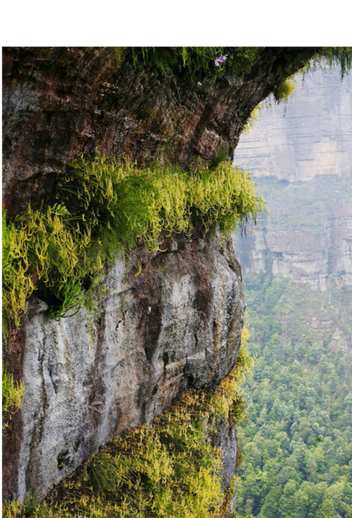

By Karen Irving Meat-eating plants seem so exotic you might imagine them deep in the Amazon or the rainforests of Borneo. But in fact the UNESCO world heritage Blue Mountains National Park boasts the most diverse range of carnivorous plants in the world, with nearly 240 species. Along the trail from Govetts Leap to Horseshoe Falls on the Emu Trekkers Blue Mountains hike, you’ll spot several varieties of carnivorous plants, including the world’s largest and most impressive display of Drosera Binata, or “sundews”. Glittering in the sunshine in huge, undulating waves of dewy, golden menace, they hug the moist cliffs beneath the spectacular 180 metre high Bridal Veil Falls. Looking like something from a James Cameron epic they hang poised ominously above the valley floor, sticky tentacles extended to lure their prey. Insects are blown along the sheer cliff face, and with year round moisture and lack of competition, the sundew have an ample source of sustenance. Conventional plants draw their nutrients from the soil, but Australia’s ancient landscapes, leached of nutrients over millions of years, have forced plants to evolve and diversify or die. Sundews have developed an ingenious method of survival and are able to grow in areas like sheer rock faces where other plants don’t have a chance. Greg Bourke has always been particularly entranced by the Drosera. "I grew up with the Royal National Park at my doorstep. I was fascinated by nature and because I was small, I think the sundews were at the right height. The interaction between plants and animals has fascinated me ever since. The struggle that occurs at the macro level is captivating to me. The Drosera Binata in the Blue Mountains are huge, much larger than those found elsewhere. They have evolved for a life on the cliffs where moisture seeps through the cracks year round.” The sundews derive their common name from the wet tentacles of mucous that cling to the meaty, glandular stalks on the plant’s surface. “The sticky mucilage secreted by the glands on the leaves is both visually attractive and pleasantly scented. This attracts the prey,” Mr Bourke explains. Once an insect lands on the sundew, it is fatally ensnared, like quicksand. As it struggles to escape, the tentacles on the leaves move in to help hold the prey and it becomes more and more stuck in its treacly coffin. Digestive enzymes are released and the nutriment is absorbed by the plant. Like a slow motion Berocca in a glass of water, they are dissolved alive from the inside out. Along the trail you’re able to get up close and personal with the sundews. Although perennial, they are best seen from spring to late summer, Mr Bourke says. “Look for trapped prey and how the plant holds it to the leaf. Also look out for Sundew Bugs, tiny insects that can move freely on the sundew’s leaves and feed on the captured prey.” But the Binata aren’t the only carnivorous species in the area. Across the cliff faces, clinging to the sandstone boulders, in pockets of scrub and moist areas or puddles along the trail, you’ll discover a wide variety of insect-eaters, which have all evolved to survive in a range of nutrient-poor habitats. About a quarter of the way along the Rodriguez Pass you’ll see the bright red rosettes of Drosera Spatulata (the Spoon-Leaved Sundew). The green Drosera Auriculata and red Drosera Peltata (Tall Sundews) are erect herbs about 30cm high. Clinging to the sandstone rocks you’ll find Drosera pygmaea (Pygmy Sundew), the tiniest species found around Sydney, often smaller than a 10 cent piece. Keen explorers will discover many varieties of Drosera in the area.

Preferring wet habitats, the Utricularias (or Bladderworts as they’re commonly known) are a different genus of carnivorous plant. They derive their name from their little bladder-like cells, which wait to suck in their prey through a hair-trigger trap door which reacts at lightning speed. They are characterised by beautiful, long stemmed flowers that have been likened to orchids or snapdragons, and come in a range of striking colours. Charles Darwin studied carnivorous plants for years, fascinated by the way they captured and consumed small insects. His studies proved the plants deliberately captured insects to gain nutriments for them, but he delayed publishing his findings for 15 years out of fear of reprisal. At the time it was considered blasphemous to suggest that a plant could eat an animal. Now it just fuels our imaginations and provides a handy template for Hollywood filmmakers to follow.

5 Comments

Bruce Hillaby

4/1/2019 06:28:24 am

Incredible plants. Right up there in wonderment with the fungi and bryophytes.

Reply

15/2/2019 01:20:23 am

The kind of diversity of plant and animal life in Australia never ceases to amaze even for us locals. The Blue Mountains National Park really deserves to be preserved and protected so the future generations can also experience these wonders.

Reply

peter Schefe

14/12/2020 11:19:29 am

Just curious where I can find the reference(s)

Reply

Peter Schefe

26/12/2020 03:23:28 pm

After much research, I have been able to find that there are currently only around 187 recognised species of carnivorous plants in AUSTRALIA, so I am curious where the 240 species in the blue mountains has come from.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsThese news updates are proudly written by Emu Trekkers' volunteer team. Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

|

ABOUT |

TREKS |

Emu Trekkers is registered as a charity with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission and is endorsed as a Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR).

ABN 82614391614.

ABN 82614391614.

© Emu Trekkers - Hike Australia. Help Kids. 2024.